Why was the Nationalist government unable to bring stability and prosperity to China?

There is no doubting that the Nationalist government under Chiang Kai-shek faced considerable problems from their 1927 conception all the way to their eventual, and perhaps inevitable, displacement at the hands of Mao’s communists in 1949. There appears to be a divide between historians : those whom conclude that the Nationalist government established a sound system of rule and good foundations for future development and democracy : only to be ruined by the invasion of and subsequent war with imperial Japan. Others contend that the government was corrupt and seriously inefficient, out of step with the vast majority of the Chinese population : most notably those in rural areas. However, ultimately it failed : and therefore the second line of argument must be taken and developed : to investigate the internal and external factors behind the demise of Chiang’s regime. The Nationalists decision to implement an old-school style of bureaucratic control at local government level, often seeing to be allied with the warlords of yesteryear proved ultimately disastrous : as did their neglect of the agricultural sector of the economy. As for stability, we may well question whether this was ever going to be possible under such a fringe regime which did so well in alienating support and distancing itself from the population at large. Ultimately, it would prove the Nationalist’s ignoring of this ‘population’ which would drive a considerable chunk of potential support into the hands of the communists, especially in the countryside - and thus the government was totally unable to bring either stability or prosperity to China.

Supporters of the Nationalist government have argued that economic depression, foreign invasion and civil strife were surely conditions beyond the control of the Nationalists. They point to achievements by the government : most notably, the positive reversal of territorial disintegration of China. Under the Nationalist government, China became more unified and centralised than ever before : albeit achieved through military means. By 1936, Chiang had consolidated political control over the greater part of the nation. However, in expanding the Nationalist’s borders so extensively : he allowed, crucially, for weakness in the provinces : and should instead have contented himself with the nominal allegiance of various provincial leaders and endeavoured to create a modern and efficient model of political, economic and social reform which may well have prevented further civil war. We may thus make a judgement concerning the failure of the Nationalist government to bring prosperity to China through analysing the economic policy and implementation of the government. The overwhelming agricultural nature of the Chinese economy must first be noted, it accounted for 65% alone of net domestic product. However, under the Nationalists - land reform and legislation was not forthcoming, the much vaunted 1930 Land Law was prevented from becoming legislation. The ratio between population and food production was somewhat addressed - the government undertook a broad and vague program to increase the farmers’ productivity through sponsoring research on new seed varieties and pesticides. However, these projects had a minimal impact - less than 4% of governmental expenditure was devoted to economic development during the 30’s. Franklin Ho wrote, rather revealingly, that “nothing went beyond the planning stage at the national level between 1927-37.” The Nationalist government thus did little to reduce rural impoverishment - which was especially acute in the wake of the 1929 World Depression and several dreadful bouts of weather. However, one may question whether the problems were indeed too great to be solved in a decade or so, certainly we must not overlook the considerably negative situation the Nationalist government was faced with.

Despite the problems faced by the government : the bitter decade of the 30’s brought about a sharp reduction in the already low standard of life for millions of Chinese people, economic hardship, in rural China especially, was endemic and worsened after 1937. Considering agriculture and other traditional based non-urbanised sectors accounted for 87.4% of the national income : it is certainly possible to criticise the Nationalist government for not implementing more reform and show real effort to tackle China’s rural problems. Of course, situations did not help : the invasion of North China especially saw a crippling of farm production and breakdown of the commercial links between town and countryside. Natural disasters further prevented the government from tackling its rural demons, such as droughts and floods, the Yangtze flooded in 1931 for example. Throw civil war into the mix, prevalent throughout the 20’s and 40’s and you have altogether a nightmare situation. Critics of the Nationalist government have thus stressed its lack of focus on rural matters resulted in its eventual demise : and point to the agricultural recovery, which by 1952 had returned output to pre-1949 levels being based on the success of a new and effective government ready to deal with agricultural matters. The largest criticism we may perhaps hurl at the Nationalist government may well be its reluctance to deal with the countryside : and focus only on the smaller urban sectors of the economy. The Ministry of Economic Affairs of the Nationalist government reported in 1937 that 3,935 factories had registered : of the factories reported, 590 only were in existence before 1937 and 3,168 had been established during 1938-42. However, even when focussing on industrial matters, the Nationalist government certainly did not produce unparalleled success. After 1942 industrial activity began to slow down due to levels of inflation and industrial output stagnated and decline especially between 1937-40. Therefore the Nationalist government crucially mismanaged the Chinese economy : from 1931 Chinese farmers experienced a sharp fall in income and a striking reversal in terms of trade - brought about dually by economic depression and governmental policies, or lack thereof.

Yet, we must not lose sight of the economic depression that undoubtedly played a significant role in creating added pressures for the government to deal with : even under communism, with the emphasis firmly on investment and research in agriculture, China’s farm output continued to lag behind. Perhaps it may well be that China had inherent problems with its economy : for instance, few of the 19th/20th Century innovations in seeds, implements, fertilisers and insecticides had found their way into rural China. Indeed, from examining land ownership statistics we may realise fully the extent of the Chinese ‘rural’ problem, which may be considered to be out of the hands of the Nationalist government. From a land survey taken in the late 1930’s of 16 provinces, the average holding of 1,295,001 owners was 15.17 mau. But the 73% of families owning 15 mau or less held 34% of the total land, whilst the 5% of families owning 50 mau or more held 34% of the total land. Therefore, economically speaking, the Nationalist government clearly made severe errors in judgement with regards to government spending, research and implementation. However, there also were existing problems facing the government : ones which had existed in China long before Chiang’s KMT came to power in 1927. Therefore, the analysis concerning the Nationalists failure to bring prosperity to China has been largely examined : however, in dealing with stability we need to delve into the party structure, maintenance and ideology.

Eastman comments, “the Nanking regime was born of factional strife and bloodshed” - indeed, the KMT consolidated its grip on power in 1927 through a mass series of killings directed towards suspected communists. Upon taking national power the regime was faced with considerable problems : all of which should be illuminated when assessing why the Nationalists were unable to bring stability to China. The government had to turn back the tide of national disintegration that had existed for over a century : a central government had ceased to exist, political power devolved into the regional hands of militaristic warlords concerned only with their own wealth and enhancement of military force. Many believed that Nationalist rule marked the beginning of a new and cohesive era of a unified, strong China. However, with regards to stability, it would be the internal power struggles combined with the external war with Japan that would make it impossible for the Nationalists to stabilise China. After 1928, once Chiang had finally consolidated his grip on the party, he proceeded to alter the character the government took. So began radical purges within the party, most notably of those on the Left : the purge of the socialists had a negative effect, leaving those members who rarely worked at grass roots level behind and removing from the revolutionary movement those with passion, vigour, discipline and commitment to the cause. By 1929 the left wing of the party had been more or less fully suppressed : Chiang’s decision to go after this element of the KMT would have important repercussions, driving into the eager hands of the communists many experienced and intelligent revolutionaries. Further to this, Chiang instructed the youth of the party, prone to left-wing idealism, to leave the party : further driving a stake between the Nationalists and the communists. Between 1929-31 the party was stripped of most of its power and ceased to play a role in the formulation of policy. Instead, Chiang relied on old-style bureaucrats and the army to consolidate his power. By 1929, 4 out of 10 ministries were headed by these types : one disillusioned member commented, upon leaving the party, “the party is nearly usurped by the old mandarin influence.” The effects of this ‘mandarin’ influence were far-reaching : lust for power, disregard for the public (especially in the countryside) and values, attitudes and practices of the old warlord regimes had been harnessed by the Nationalists : a crucial error, and one which contributed immensely to the governments inability to provide any stable platform for political and economic growth.

Indeed, even as late as 1946 - reformers surveyed the corruption of their government and attributed it to the political opportunists and bureaucrats favoured by Chiang throughout the period of rule. Furthermore, the pervasive influence of the army proved deeply unpopular : under Nationalist rule, the army became the preponderant element of rule rather than the government or party. Strikingly, of the party leaders (members of the Central Executive Committee) 43% in 1935 were military officers. 25 out of 33 Chairmen of the provinces controlled by the Nationalists between 1927-37 were generals. Connected with the importance of the military to the Nationalist regime was the militarism of the various provinces dealt with by Nanking. Chiang’s crucial mistake was to institutionalise the position of the provincial militarists, thus allowing these warlords to become autonomous organs that legitimised their regional dominance, and inadvertently continuing the ‘rural’ problem that so afflicted rural China. Of course, many were defeated in battle, which served only to further the instability and chaos throughout the nation : such as the victories over the Kwangsi in 1929 and the Northern Coalition in 1930. Perhaps even more significantly however, was the invasion of Japan in 1931 and subsequent war after 1937, which seriously economically destabilised the nation and served to exacerbate China’s internal problems, despite initial attempts to ‘come together’ in the face of the imperialist foe.

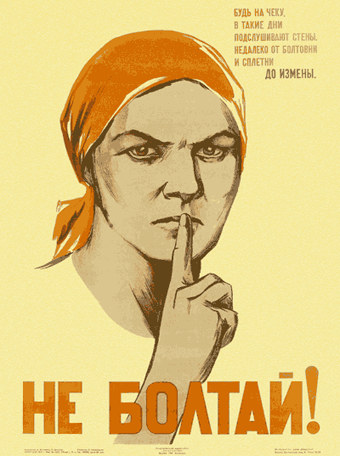

However, aside from external factors such as the Sino-Japanese war, institutional factors too played their part in the Nationalists’ inability to bring stability to China. Franklin Ho wrote, “the real authority of the government went wherever the generalissimo [Chiang] went.” As a result of this the government, as a policy-formulating and administrative organisation, languished. Much of the civilian apparatus within the legislative branch of government had neither the finance nor power to implement its proposals. The civil government remained subordinate to the interests of Chiang and the military : which created even more of a chasm between the Nationalists and much of public opinion. Further to this, the Nationalists targeted particularly politicised groups such as trade unions and students for repression. After 1927, the leadership of China’s labour unions was replaced with agents of the regime and independent union activities prohibited. Also during the student revolts of 1931-2 and 35-6 thousands were thrown into prison and students were terrorised by the presence of government informers in their classes. The Nationalists thus alienated them and pushed these groups politically leftward, many allying with the communists. This push leftwards played into the hands of a group long-repressed by the Nationalists : who, in stark contrast to the government, exercised an extremely successful policy of popularising and supporting peasant movements in the Chinese countryside. The communists could not have won power in 1949 without the peasant armies and support of so many villages. Equally so, without the communists, the peasants would never have conceived the idea of revolution : therefore the two are inextricably inter-twined. Disillusioned communists successfully channelled energies into the three major peasant discontents : rent, interest and taxes and they successfully prevented an alternative to the Nationalists whom were seen to identify only with the landlords in the countryside. Bianco draws attention to the marked increase in riots with relation to tax during the Nationalist government’s tenure. There was also a significant number of other anti-fiscal riots : their targets, usually governmental civil servants and tax collectors. The communists clearly realised the military potential of the peasantry : clearly showcased from events such as the Lung-t’ien incident in December 1931 when tens of thousands of peasants attacked a detachment of 2,500 soldiers. Thus, the peasants, without possessing a strong sense of class consciousness were clearly disillusioned with Nationalist rule : the spontaneous orientation of peasant anger suggest they were far more conscious of state oppression than of class exploitation. The sheer scale and variety of disturbances clearly highlights the peasantries alienation from the Nationalist state : the communists’ vital achievement was thus in turning this potential into action. One man crucially responsible for uniting communists with peasant communities was P’eng P’ai whose overall success was remarkable. He discovered that setting up a peasant associated proved difficult at first - but once the step was taken to address the peasants on their level about issues that primarily concerned them, members flocked : the communists won peasants and artisans over to their organisations by adapting to the peasant’s world : something which the Nationalists more than failed to do. No link existed between the Nationalists and the peasants : a vital reason in the reasoning behind the inability of the government to bring stability or prosperity to China.

Throughout the Nationalist reign, the civil bureaucracy remained corrupt and inefficient : the government failed to identify with the people, but rather stood above them. The crucial error on behalf of Chiang’s government lay in not allowing the politically mobilised elements of society to become involved in the processes of government. The communists had begun providing the organisation that could convey peasant discontents into political power : but the Nationalists had the chance to turn the countryside into a powerful ally : instead it allowed it to become economically impoverished and politically hostile. Over-bureaucratisation, economic mismanagement, general inefficiency and too many links with the ‘warlords’ of old created innumerable problems for the Nationalist government. Add to this already long list the extensive external problems faced by Chiang’s government - such as severe economic depression and invasion from imperial Japan and it becomes no great surprise that the Nationalist government was unable to bring both stability and prosperity to China.

Wednesday, 28 April 2010

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment